TALENT OR JOB

J. G. Estoya

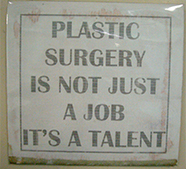

I walked down the familiar halls of the operating room complex, unperturbed by the rush of activity even at that early hour of the morning. As expected, it was going to be another busy day. As I stepped into the operating theatre assigned to me, the sign plastered on the door caught my attention. The words inscribed on the small-sized poster had been printed using the first generation of computer printers. It must have hung on that door for quite a number of years before I came to the hospital. Mindlessly, I have passed by it countless of times; I have read it a handful of times; and yet, it was only at that moment that the words really seized me. Now that I am about to finish my fifteen years of University education with six years of surgical training. The sign read, "Plastic Surgery: it's not just a job, it's a talent."

Back to Articles

Most - if not all - of us who decide to join the Department of Surgery of the State University have our individual academic merits to support our claim to excellence. Despite that, in the surgical world where skills and academic proficiency can be mutually exclusive, nobody at the outset of his training can really predict his fate as a physician with the knife. I can clearly remember a good friend and comrade who, in a moment of self-doubt and anguish, ushered me to a corner and asked my opinion of his surgical skills. His academic stature was undoubtedly beyond question. Yet, there is always that lingering issue of the "hands following the mind," so to speak. Meaning, can the hands be taught to execute the knowledge that is in our mind? And if so, to what extent and degree? Such a show of vulnerability that my friend manifested, every neophyte surgeon can identify with, including myself, of course. Only through time and experience will self-awareness be revealed.

Plastic Surgery is of special interest. It is a field where, literally speaking, results speak for themselves. Nobody can hide a graft loss or a failed flap. An uneven eyelid or a twisted jaw is obvious. It is a surgical specialty where even the last few millimeters of correction can be vividly apparent and subsequently criticized. And what's more, patient expectations are exceedingly high. Thus, it is not just a job! But who is fortunate enough to have the talent to do the job? In the practice of Plastic Surgery, as in the arts or sports, when you are not at your best, you are nobody. Consider, for instance, those who play the piano or those who fight boxing. There are pianists who perform at the Cultural Center while there are those who play at some bar downtown. There are many Filipinos who take up boxing as a sport, and yet only a very few are able to join the world championship. In these endeavors, the disparity between the excellent and the mediocre is so wide. No category or class ever falls in between. So is it true with Plastic Surgery. Plastic surgeons cannot settle for anything less than the very best. In contrast, college professors, internists, or general surgeons (no offense please) - even in cases where they may be only merely capable - will still be able to lead a fulfilled professional life based on the outcome and expectation of their work.

What if, after all those grueling years of training, we realized that we didn't have the talent? Shall we simply be resigned to the fact that we are a living tragedy? Without exception, all Plastic Surgery graduates contend with this question despite having been accepted and trained at a reputable institution. Perhaps they can persevere to address this issue and learn to improve themselves. Others have reinvented themselves and have compensated for whatever weaknesses they have realized along the way. This is the most honorable thing to do. Besides, excellent decision-making on the part of an intelligent and prudent surgeon is still essential and is oftentimes preferable to one who simply has the skill in wielding the knife. As my mentor would say, "The most splendid result of a plastic procedure is a premium of two things: proper planning (having a full grasp of the problem coupled with full armamentarium of knowledge) and precise execution (talent!)."

Hence, we all desire to have both the knowledge and the skill - in equal, robust proportion. Whatever inherent limitations come our way can be remedied by adequate training and a positive attitude. No graduate is gratuitously condemned into the oblivious state of mediocrity. Still, however, while others are doing the job, some of us are simply performing our talent!